Opening Quote

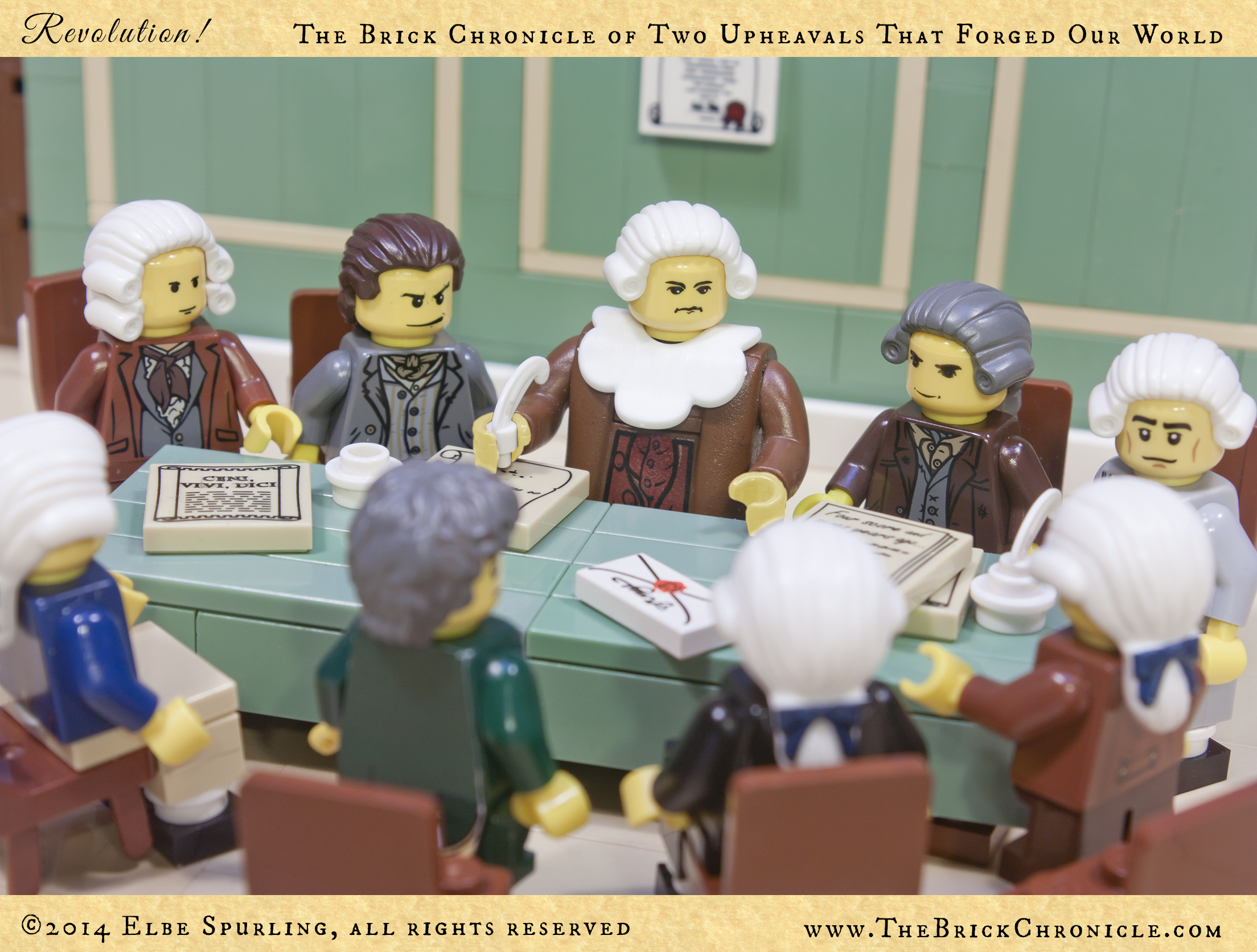

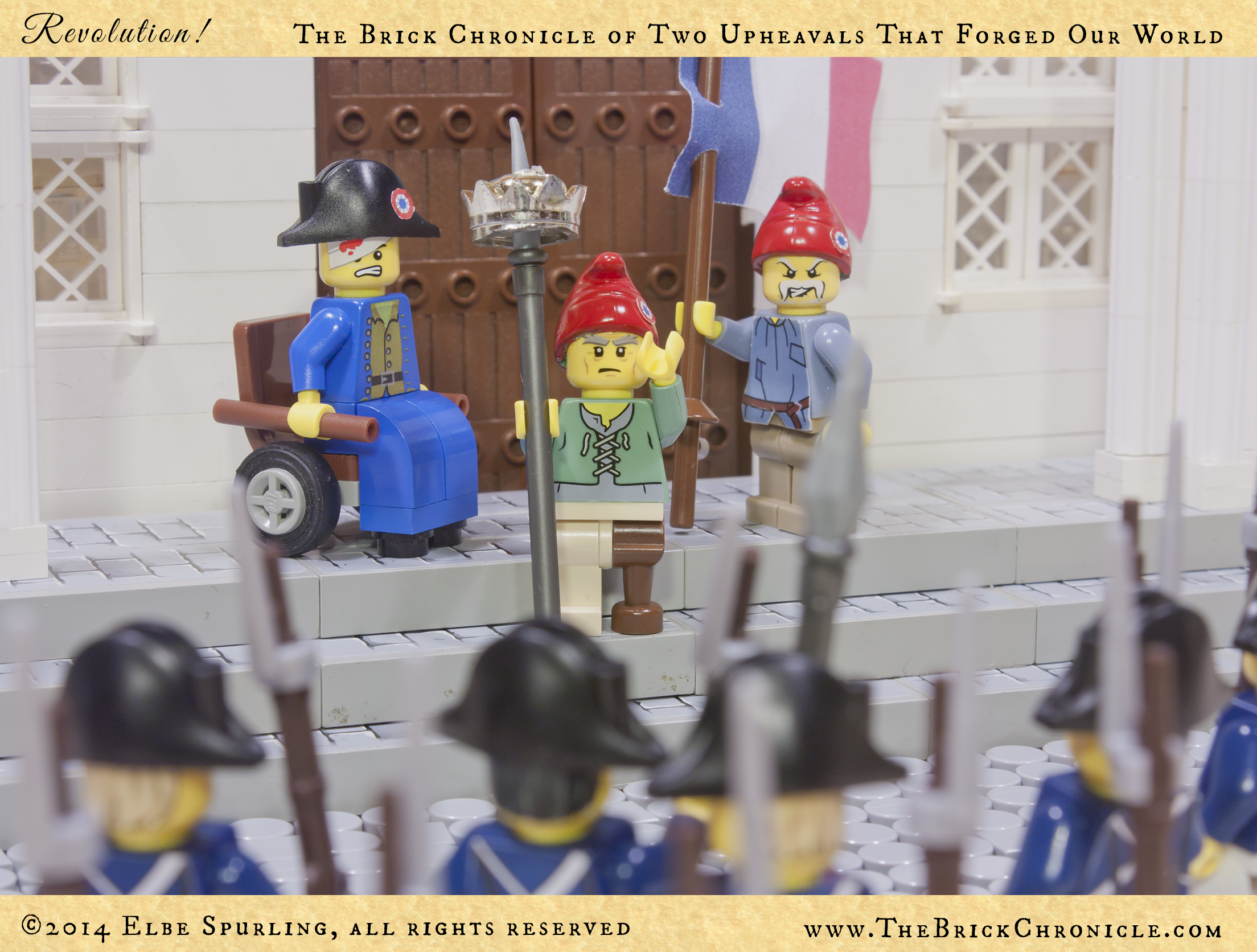

chapter_14_image_01

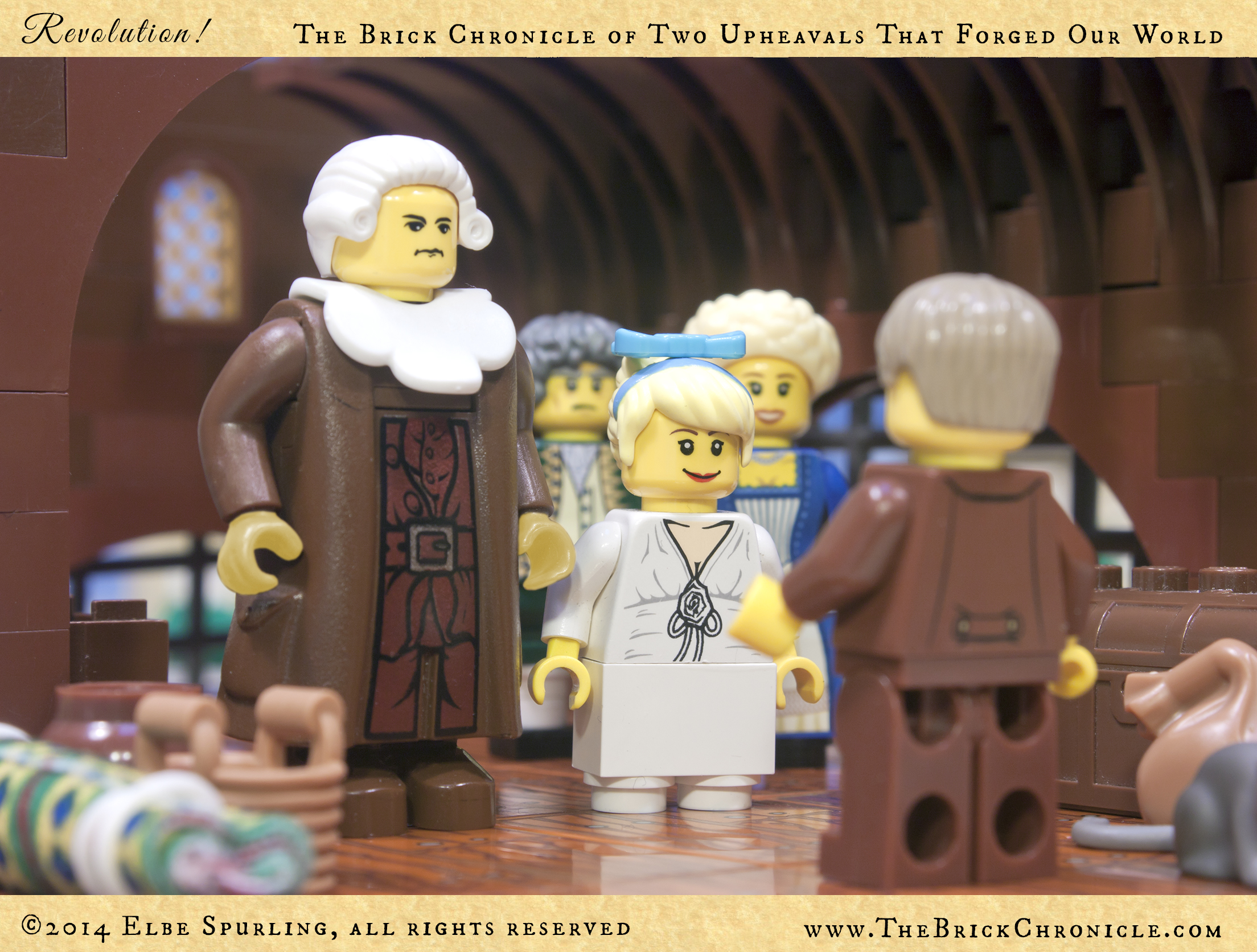

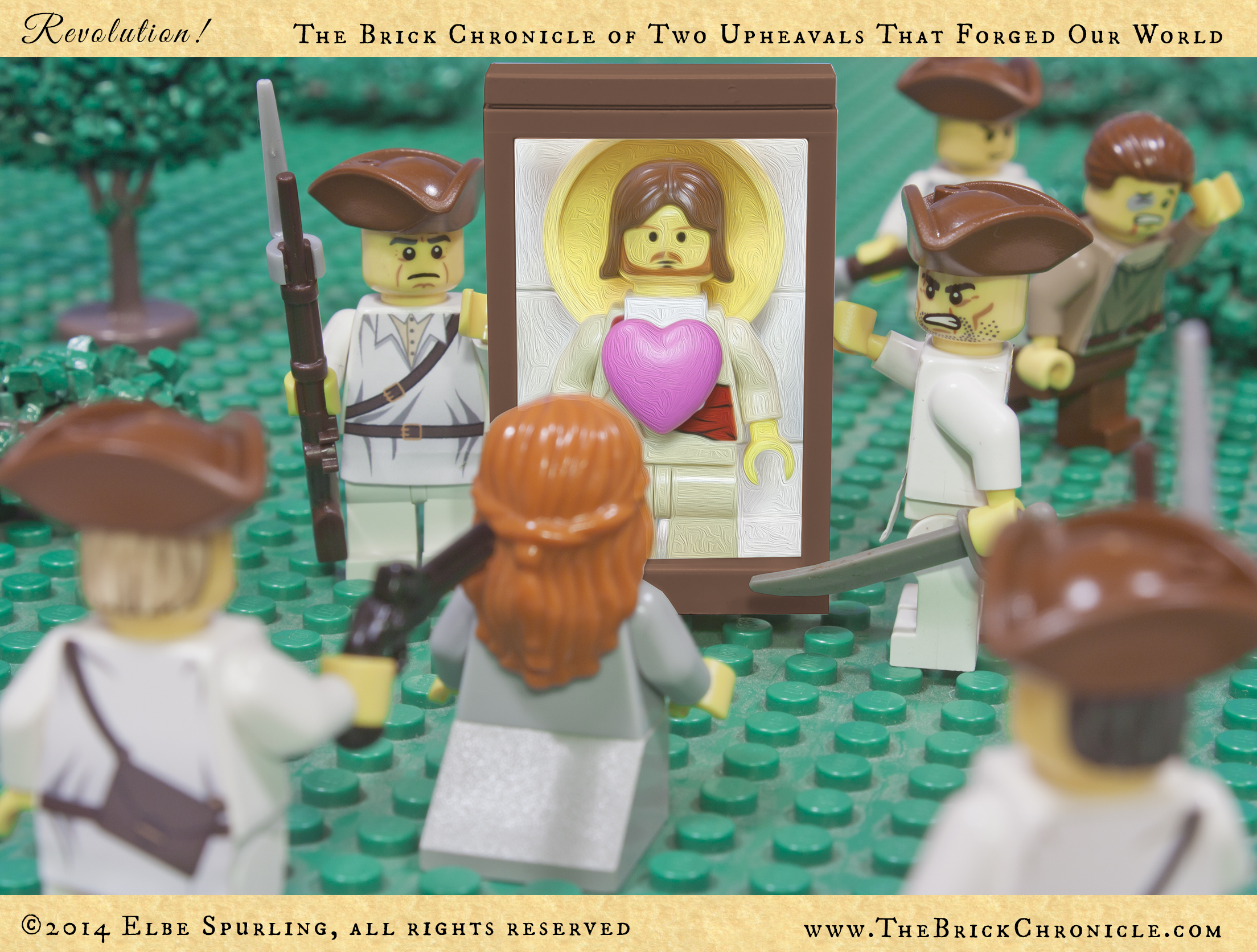

chapter_14_image_02

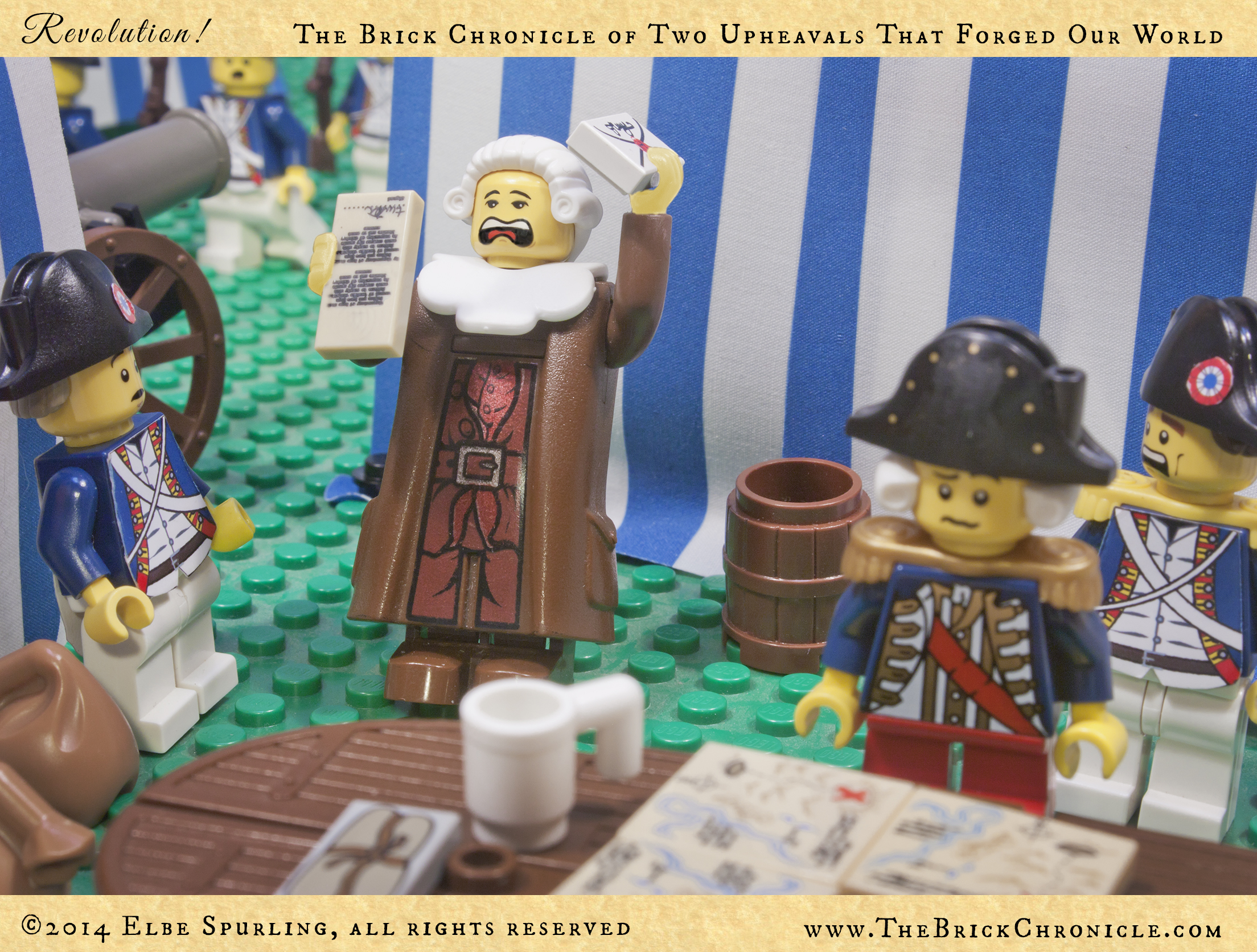

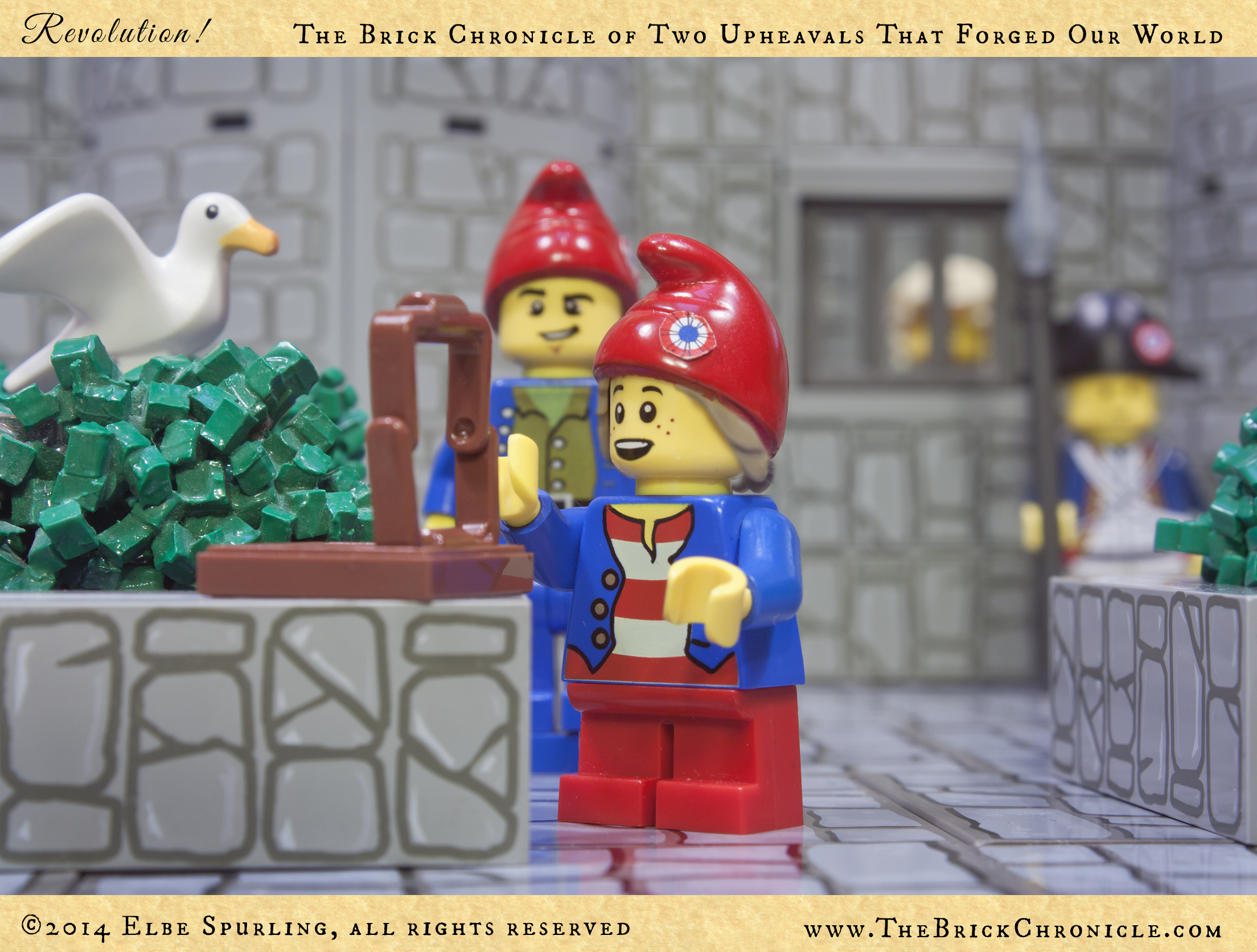

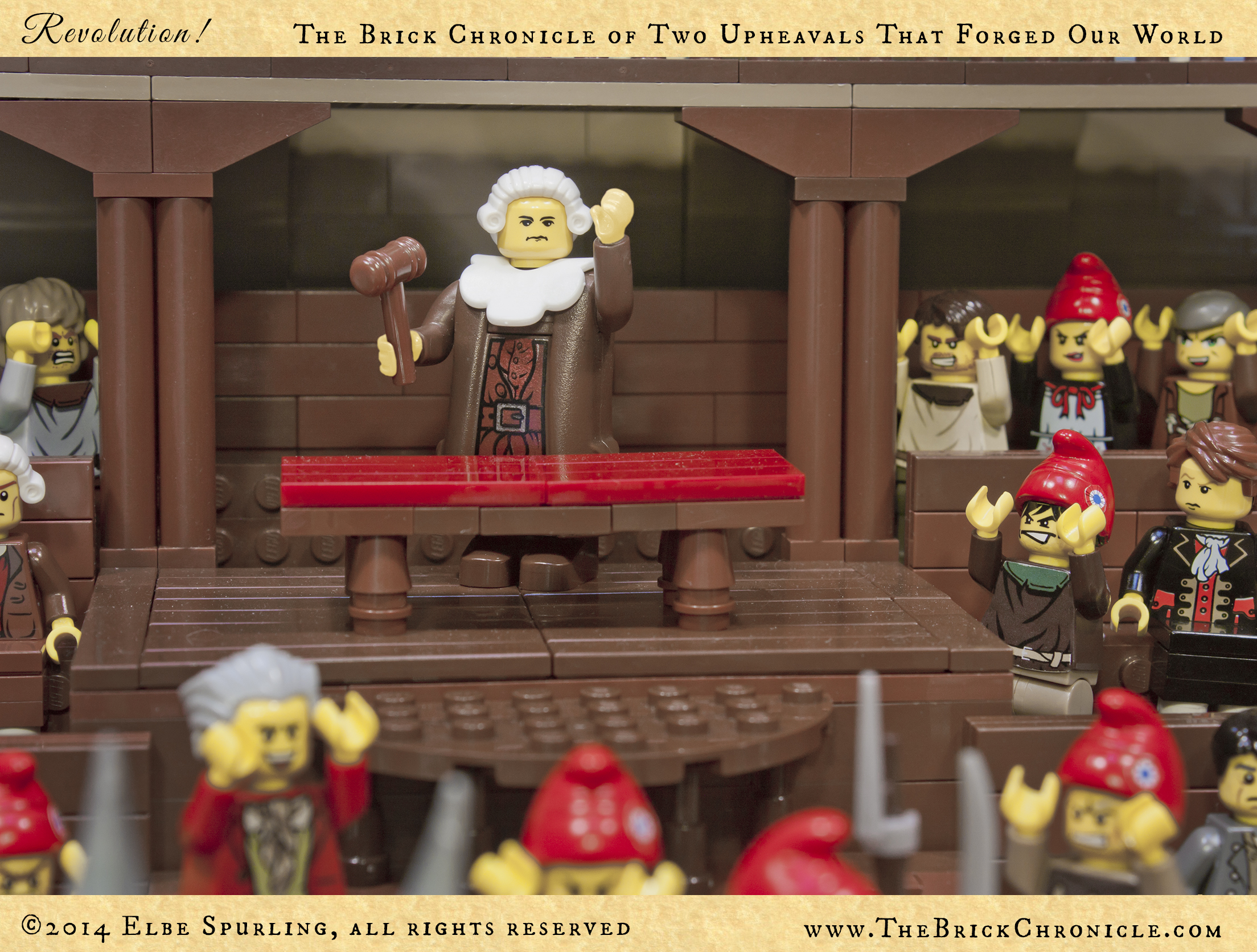

chapter_14_image_03

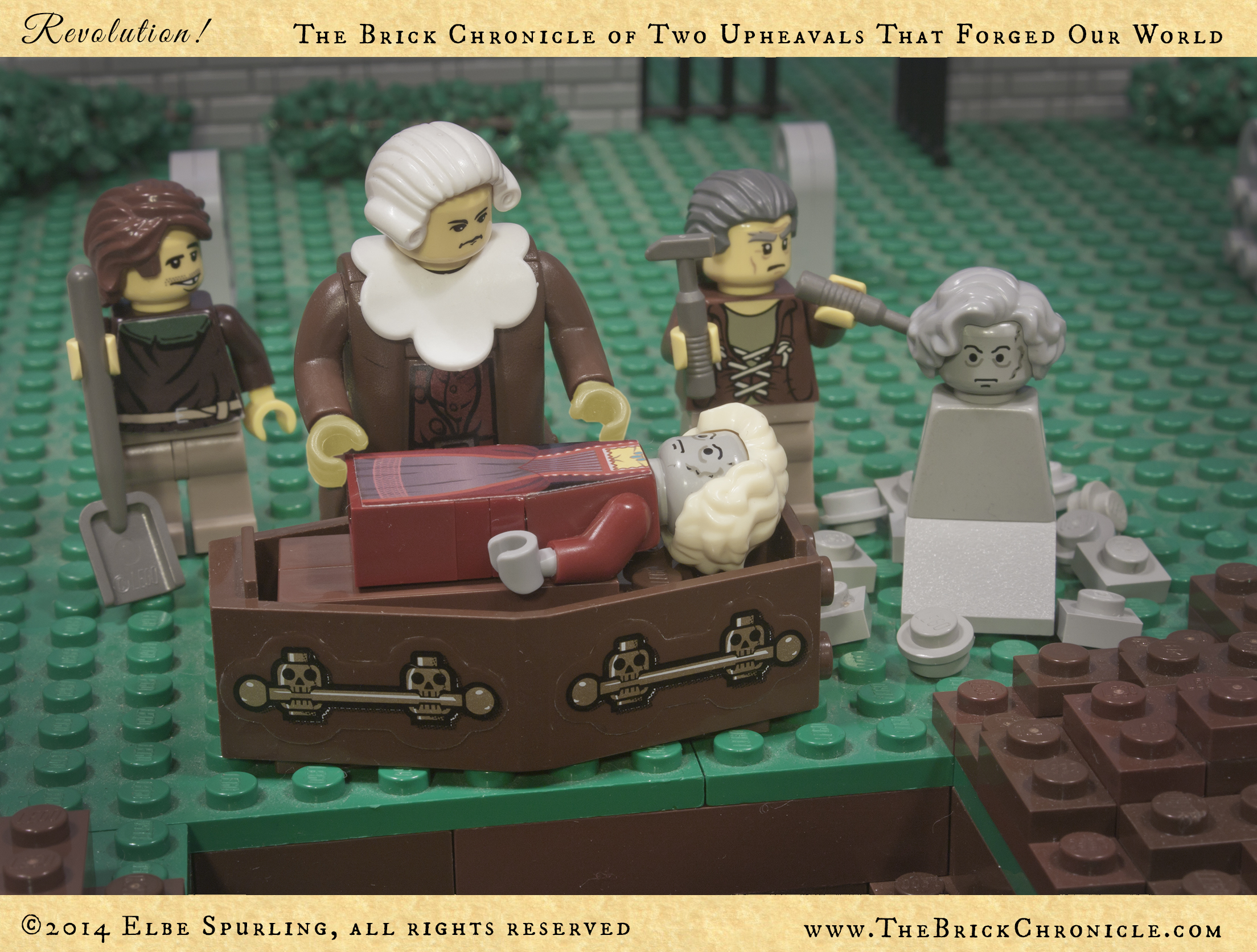

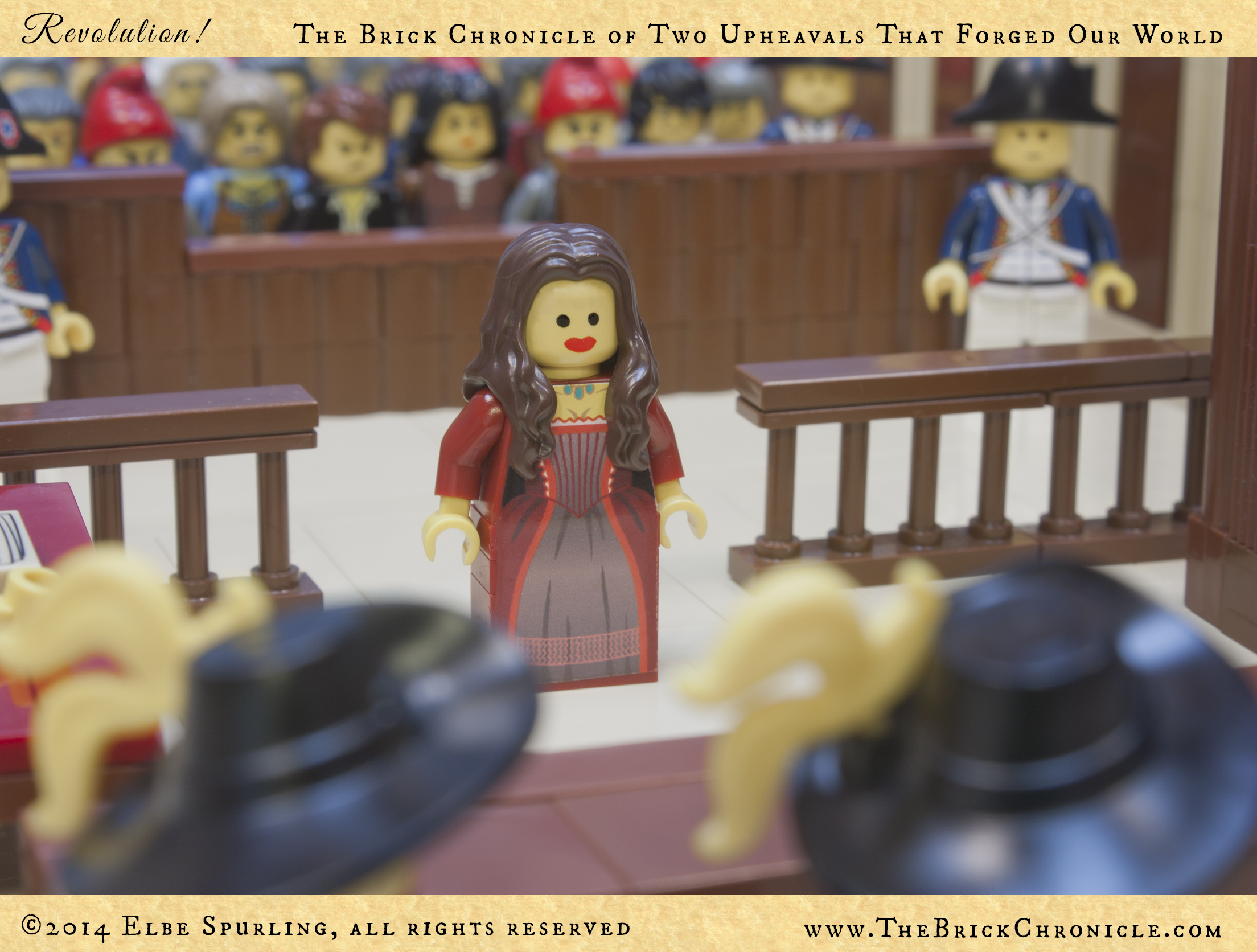

chapter_14_image_04

chapter_14_image_05

chapter_14_image_06

chapter_14_image_07

chapter_14_image_08

chapter_14_image_09

chapter_14_image_10

chapter_14_image_11

chapter_14_image_12

chapter_14_image_13

chapter_14_image_14

chapter_14_image_15

chapter_14_image_16

chapter_14_image_17

chapter_14_image_18

chapter_14_image_19

chapter_14_image_20

chapter_14_image_21

chapter_14_image_22

chapter_14_image_23

chapter_14_image_24

chapter_14_image_25

chapter_14_image_26

chapter_14_image_27

chapter_14_image_28

chapter_14_image_29