Opening Quote

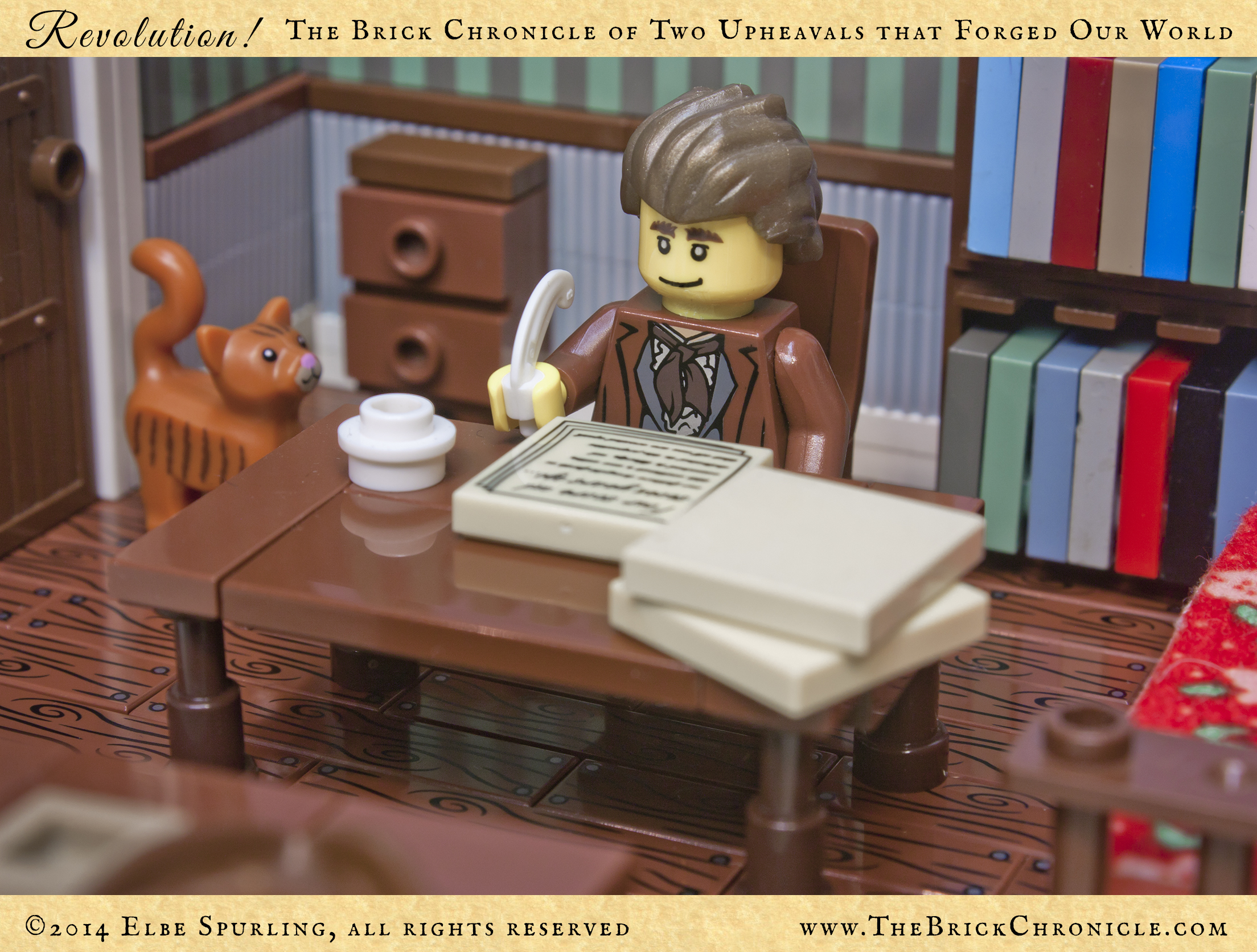

chapter_04_image_01

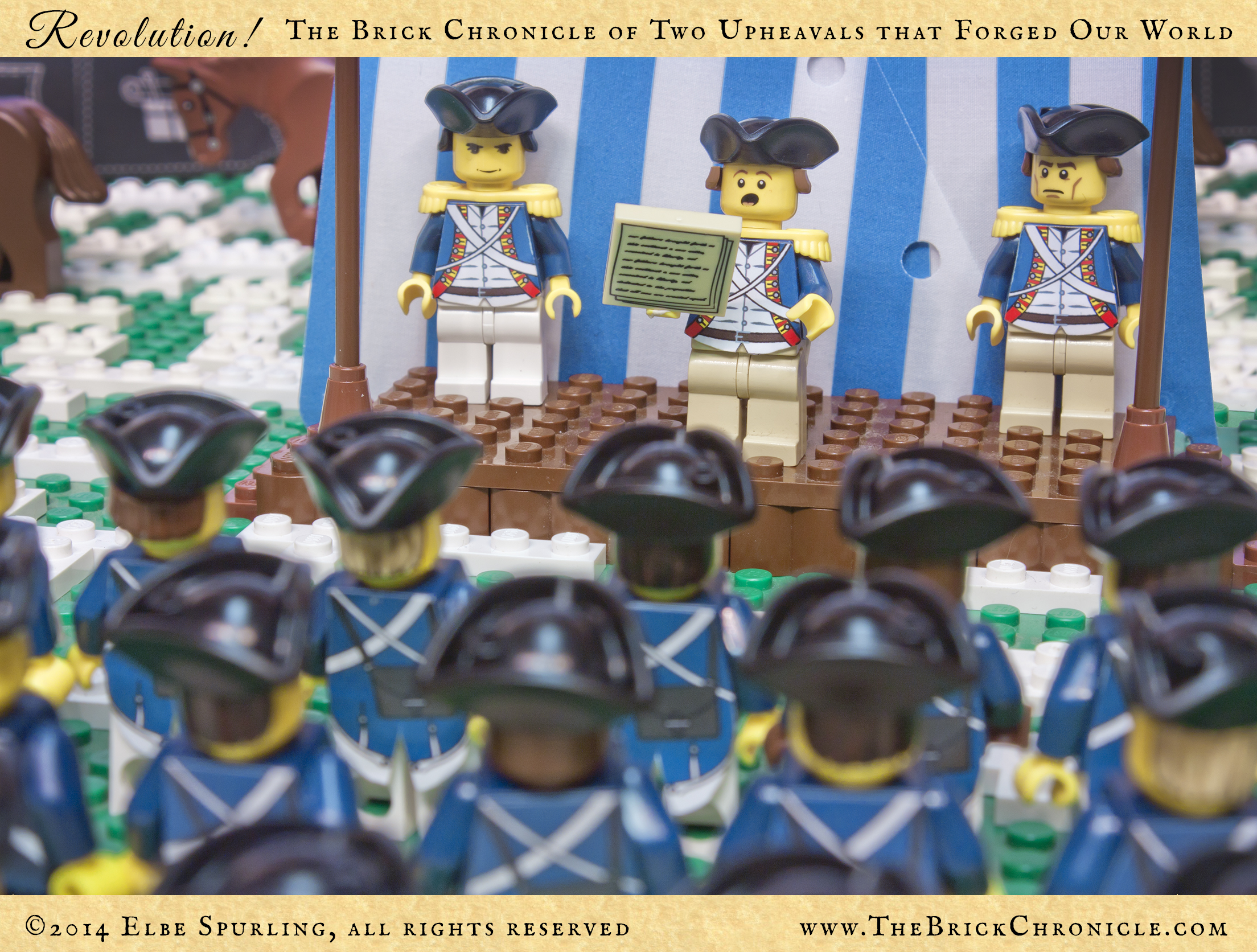

chapter_04_image_02

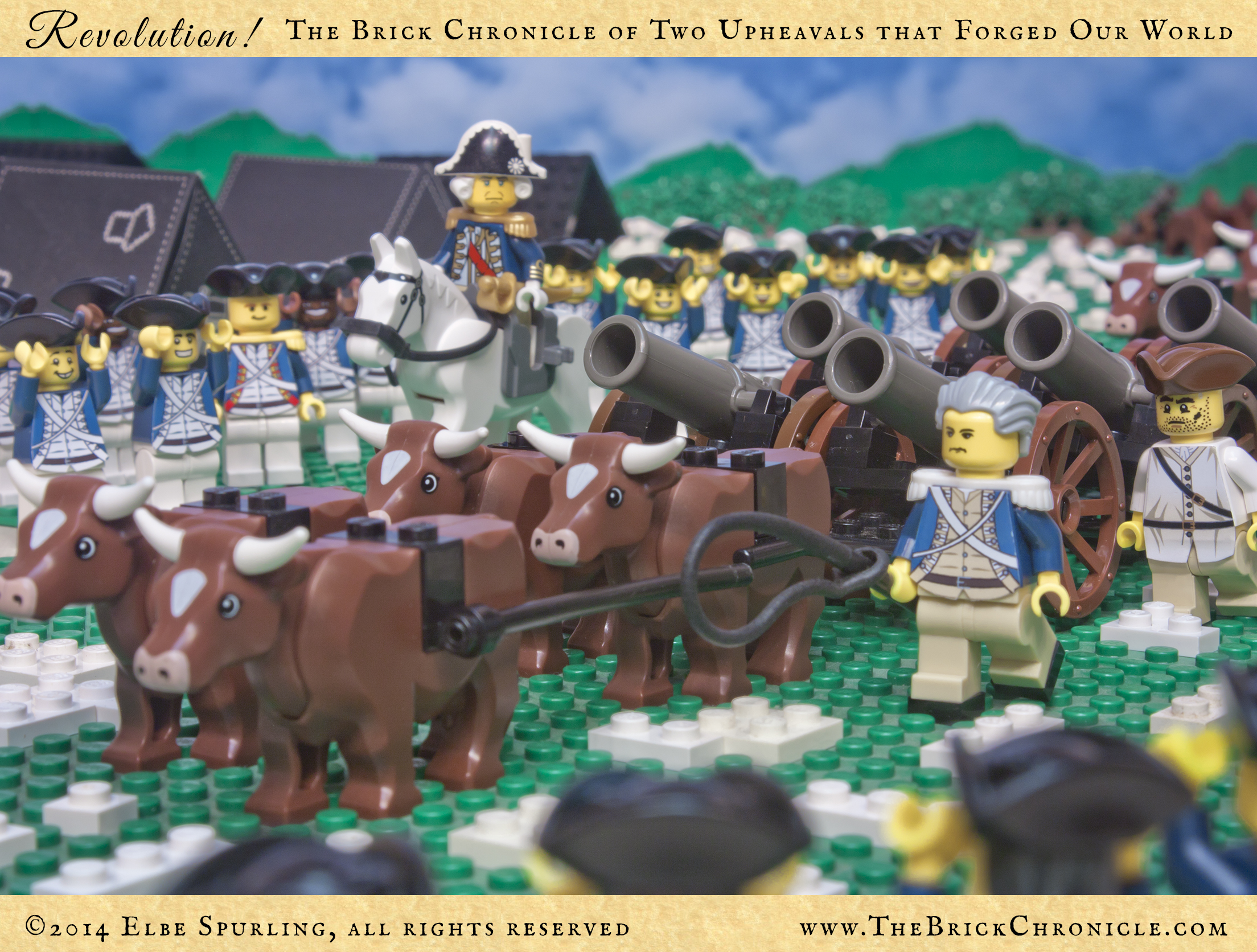

chapter_04_image_03

chapter_04_image_04

chapter_04_image_05

chapter_04_image_06

chapter_04_image_07

chapter_04_image_08

chapter_04_image_09

chapter_04_image_10

chapter_04_image_11

chapter_04_image_12

chapter_04_image_13

chapter_04_image_14

chapter_04_image_15

chapter_04_image_16

chapter_04_image_17

chapter_04_image_18

chapter_04_image_19

chapter_04_image_20

chapter_04_image_21

chapter_04_image_22

chapter_04_image_23

chapter_04_image_24

chapter_04_image_25

chapter_04_image_26

chapter_04_image_27

chapter_04_image_28

chapter_04_image_29

chapter_04_image_30

chapter_04_image_31

chapter_04_image_32

chapter_04_image_33

chapter_04_image_34